Writing wisdom from author C.S. Lewis

Stay on the road with these three tips gleaned from Lewis’ writing.

Tom Corfman is a senior consultant with Ragan Consulting Group, where good triumphs in the Build Better Writers program, just like in Narnia.

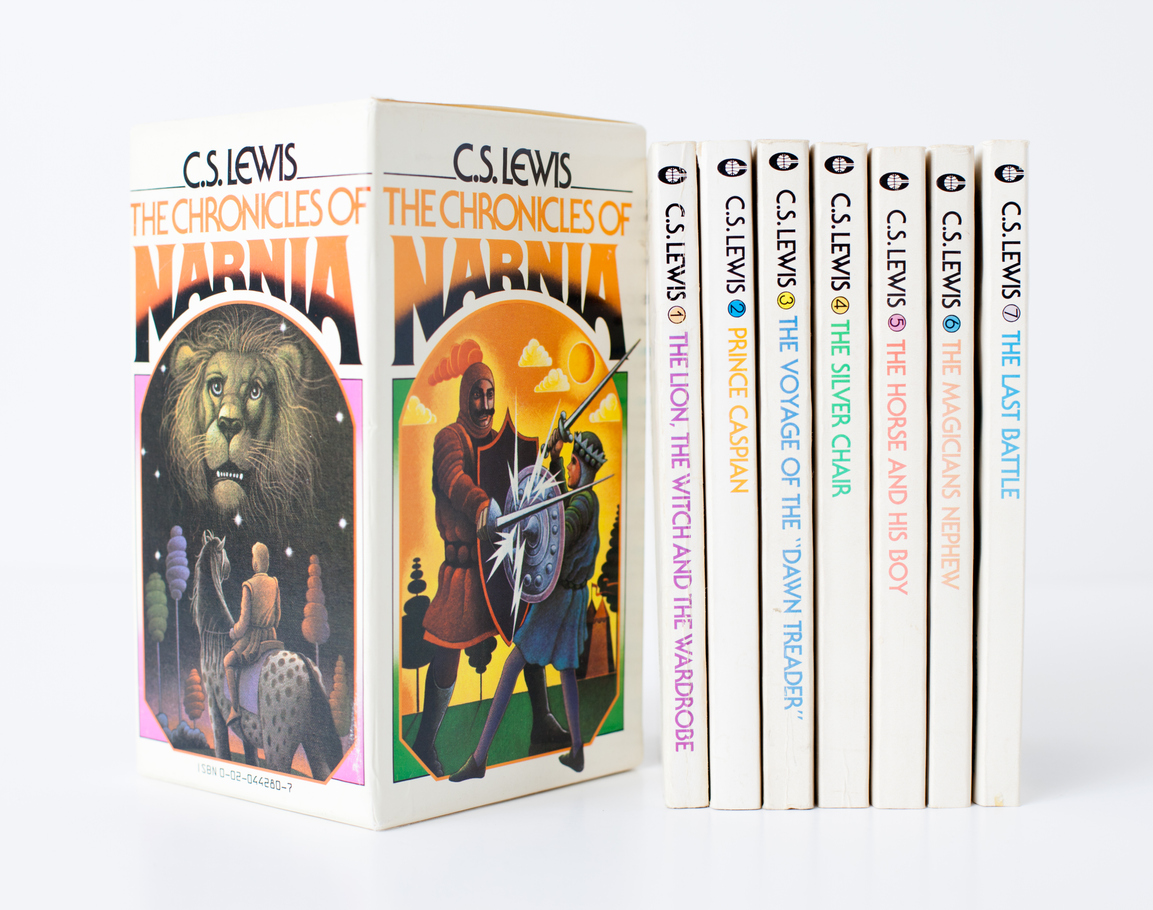

Best known for the “Chronicles of Narnia,” C.S. Lewis’ insights into the craft of writing were honed by his versatility, making him relevant to professional communicators who have more down-to-earth concerns than a lion named Aslan or a White Witch.

Lewis, who died in 1963, wrote literary criticism, theology, memoir and poetry as well as fiction. In thinking about technique, he emphasized helping the reader understand.

“I sometimes think that writing is like driving sheep down a road,” he said that same year. “If there is any gate open to the left or the right, the readers will most certainly go into it.”

In a letter to a novelist in 1937, he described a chapter this way: “This is crisp as grape nuts, hard as a hammer, clear as glass.”

Many of the lessons that we teach in our own Build Better Writers program can be found in “C.S. Lewis on Writing (and Writers),” a collection published late last year. It was edited by David Downing, a Lewis scholar and professor at Wheaton College in suburban Chicago.

We’ll try to keep everyone on the road with these three tips gleaned from Lewis’ writing.

1. Jargon in the Garden. Technical terminology and faddish phrases grow like weeds if not removed quickly and regularly from your copy. We recommend using the linguistic version of a handheld cultivator to excise the tiresome words, which choke out the meaning of your sentences.

But they keep popping up. Apparently, an explanation for their removal is still needed. Business buzzwords quickly become cliches and then drained of any meaning by overuse. People use them without knowing their meaning.

Technical terms have their place but should be used sparingly. When they’re necessary, they should always be explained, whether you’re writing for employees or the public.

“We might have only the foggiest idea of what these phrases mean, but we’re hesitant to request clarification for fear that we’ll appear ignorant or out of touch,” Laura Cassiday, a senior writer for the NeuroLeadership Institute, wrote in June.

Lewis touched on this when responding to an aspiring American writer who was a fan of the Chronicles, published from 1950 to 1956. He offered five tips on writing, including these two closely related suggestions.

“Always prefer the plain direct word to the long, vague one. Don’t implement promises, but keep them,” Lewis wrote. “Never use abstract nouns when concrete ones will do. If you mean “more people died,” don’t say “mortality rose.”

“Implement” has long been on our list of “weed words.” New additions are “around,” when you mean “about,” and “socialize,” when you don’t mean spending a pleasant time with friends or associates.

2. Better reporting. Jane Gaskell’s very successful career as a fantasy writer began in 1957, when her first novel was published at age 16. “Strange Evil” was a hit, prompting Lewis to write her a fan letter.

He called the book a “quite amazing achievement” and offered some unsolicited advice. Never use adjectives or adverbs which are mere appeals to the readers to feel as you want them to feel, he wrote. They won’t do it just because you ask them: you’ve got to make them. He continued:

“No good telling us a battle was ‘exciting.’ If you succeeded in exciting us, the adjective will be unnecessary: if you don’t, it will be useless. Don’t tell us the jewels had an ‘emotional’ glitter; make us feel the emotion. I can hardly tell you how important this is.”

Show the reader, don’t just tell. We often find that problems in writing stem from holes in the reporting. We resort to adjectives because we don’t have the details, the color we need to paint a picture.

3. Reverse engineering. In our workshops, we sometimes ask participants to rewrite a famous quote in the best (or worst) example of corporate speak or bureaucratese. We use examples such as President John F. Kennedy’s “Ask not …” line from his Inaugural Address.

The results are entertaining, as professional communicators demonstrate their mastery of the lingo that swirls through emails, memorandums and reports.

To explain writing style, Lewis offered a reverse-engineered sentence in a letter to Arthur Greeves, a lifelong friend who grew up on the same street as Lewis in Belfast, Ireland.

Style is “the art of expressing a given thought in the most beautiful words and rhythms of words,” Lewis wrote.

To demonstrate, Lewis produced this: “When the constellations which appear at early morning joined in musical exercises and the angelic spirits loudly testified to their satisfaction.”

It’s Job 38:7 from the King James Bible.

Do as I say?

Clive Staples Lewis, known as Jack, and J.R.R. Tolkien, were close friends for more than a decade. The two World War I vets with a shared interest in medieval literature met in 1926 on the faculty of Oxford University.

It’s been said without their friendship, the Chronicles and “The Lord of the Rings” would not have been written. Yet Lewis’ writing style wasn’t Tolkien’s cup of tea.

“Lewis is always apt to have rather creaking stiff-jointed passages,” Tolkien wrote in a 1938 letter to Lewis’ publisher.

Perhaps Lewis didn’t always follow his own advice.

Follow RCG on LinkedIn and subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.